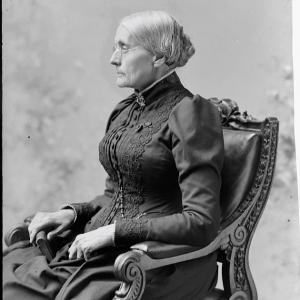

Susan B. Anthony

Anthony was born in 1820 in Massachusetts. She was raised as a Quaker and her belief in equality inspired and guided her throughout her life’s work.

Anthony fought for the abolition of slavery. In 1856, she served as an American Anti-Slavery Society agent, making speeches, organizing meetings, and distributing pamphlets.

In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the two suffragists worked to gain independence and equality for women for the rest of their lives. She traveled around the country advocating for women’s rights and lobbied Congress every year until her death.

She died in 1906, fourteen years before many women were given the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

“It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people - women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government - the ballot.” - Susan B. Anthony, 1873

Early Life

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, near Adams, Massachusetts to Daniel Anthony and Lucy Anthony. She became a part of the rapidly expanding young American republic founded less than fifty years before. As settlers continued to push westward, the expansion of the nation led to questions concerning the establishment of slavery in the West. This was exemplified by the passage of the Missouri Compromise in the year of her birth.

The industrial revolution was beginning in America. Cotton cloth was the new sensation and the demand for it began to steadily grow. In fact, Anthony’s father built a cotton factory and employed many young women, some of whom boarded with the family. Anthony even worked at the mill with one of her sisters, splitting their wages. But an early age, Anthony wondered why her father would not employ a woman as an overseer in the factory (International Council of Women 163).

Anthony was influenced by the political, social and economic issues of her time, but was especially influenced by the religious views her family instilled in her from an early age. Her father Daniel was a member of The Society of Friends, or Quakers. He was concerned over the westward expansion of slavery, and she often heard him say that he tried to avoid purchasing cotton raised by enslaved labor. This early understanding of the horrors of slavery stayed with Anthony throughout her life (Lutz 10).

A few weeks after her thirteenth birthday, Anthony officially became a member of the Society of Friends. One of their main values is “the equality of all people before God” (Lutz 11). Quakers not only encouraged but demanded education for both boys and girls. As soon as Anthony was old enough, she worked and taught in the “home school” during the summer, educating younger children. Further expanding her education in 1837, Anthony's father sent her to the Friends’ Seminary near Philadelphia, where she studied a variety of subjects: arithmetic, algebra, literature, chemistry, philosophy, physiology, astronomy, and bookkeeping.

Abolition for All

In 1845, the Anthony family moved to Rochester, New York, where they became active in the anti-slavery movement. Their home served as a meetinghouse almost every Sunday, and attendees included famous abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison.

In her mid-thirties she was invited to join the anti-slavery lecture circuit during a defining period in US history – the decade of crisis before the Civil War. During this time, Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the new Fugitive Slave Law was passed, and the pending Kansas-Nebraska Act infuriated northerners and abolitionists.

Anthony spoke out against slavery wherever she could find an audience. She even challenged Abraham Lincoln’s moderate position on slavery in 1861, demanding “no compromise with slaveholders.” It was a chapter in her life she would later call “The Winter of Mobs”. In fact, in Syracuse, New York, a mob burned her in effigy and her “body” was dragged through the streets (Sherr 30).

Later, in 1863, Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucy Stone formed the Women’s Loyal National League to press for a Constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. This goal was finally realized with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

The Ballot for Women: The American Suffrage Movement

In 1848, Anthony began work as a teacher in New York and became involved in the teacher’s union. Through this, she discovered that male teachers received a monthly salary of $10, while the female teachers only earned $2.50 a month. This experience with the teacher’s union, along with her previous abolition activism and Quaker values, inspired her dedication to gender equality. She would go on to become greatly involved in the fight for women’s suffrage, or the right for women to vote in elections.

In 1851, she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton was known for organizing the first woman's rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention, in 1848. Stanton and Anthony formed a friendship and partnership that lasted the rest of their lives. While Stanton, a mother of seven children, would often stay home to write and organize, single Anthony had the freedom to travel as an activist. Though she received several proposals of marriage throughout her life, Anthony never married (Sherr 14).

In the 1850s and 60s, Anthony was extremely active in the women’s rights movement. She served on committees, spoke at conventions, created women’s associations, and campaigned for women’s property rights.

In 1868, Anthony and Stanton founded the American Equal Rights Association and became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. Anthony built subscriptions, solicited advertisements, and took copies to the printer. The paper discussed suffrage, education, marriage and divorce, equal pay, eight-hour workdays, and labor and financial policy.

A Split in the Movement

It was at this point that the suffrage movement divided over the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments. The 14th Amendment was the first mention of gender in the Constitution, granting all male citizens 21 years old the right to vote. The 15th Amendment stated that the right to vote would not be denied due to race. The passage of both meant that Black men would have the right to vote, but not Black women or other women of color.

Anthony and others supported the 15th Amendment only if it included universal suffrage for all, regardless of race and gender. Activists like Frederick Douglass and Lucy Stone still supported the 15th Amendment, because they thought it would be impossible to get the vote for both Black men and white women at the same time. But Stanton and Anthony disagreed and opposed the amendment, believing that if anyone deserved the vote, it was the educated white women first. Though Anthony had previously lobbied for the abolition of slavery and the rights of enslaved African Americans, she still adopted the racist positions used by many other white women at that time to support her goal of women’s suffrage.

To focus attention on women’s suffrage, and in reaction to the exclusion of women in the 15th Amendment, Anthony called together the first suffrage convention ever held in Washington, DC in January of 1869. Then, on March 15, 1869, the first federal women’s suffrage amendment was proposed in Congress for consideration (Lutz 115).

That same year, Anthony and Stanton split from other suffragists like Lucy Stone and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and created the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) which opposed the 15th Amendment since it did not include gender. Anthony adamantly continued her opposition as editor of The Revolution. Stone, Watkins Harper, and other suffragists formed the rival organization, American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported the 15th Amendment, while also advocating for women’s suffrage in consequent legislation. These opposing groups vied for support up until the 15th Amendment was finally ratified in 1870. The NWSA then refocused its energy to push for a separate constitutional amendment aimed at specifically securing women the right to vote.

The Trial of Susan B. Anthony

After the Civil War, suffragists had four major legal strategies: campaigning at the federal and state level; lobbying to supportive voters and their casting of ballots; proposing a new women’s suffrage Constitutional amendment; and litigating in court to test women’s rights under the existing Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Anthony preached militancy to women throughout the presidential campaign of 1872, urging them to claim their rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments by registering to vote in every state of the Union (Lutz 140). During the campaign, Anthony, her sisters and a close Quaker friend walked to a nearby barber shop to register to vote and eleven other women joined them. The women boldly entered and the bewildered male registrars allowed them to sign in. Then on the morning of November 5th, she cast her first and only presidential ballot for the Republican candidate Ulysses Grant and two congressmen. Weeks later, on November 18th, she was arrested at her home in Rochester, New York by a US marshal and put on trial at the Ontario County Courthouse. She and her colleagues all pleaded “not guilty” and bail was set.

For three weeks she traveled around the county, delivering lectures on the “crime of a citizen voting in an election”. The prosecutor complained and the trial was moved to another county. On June 17, 1873, Anthony was tried by 12 white men in the jury box, but the judge made his decision before even hearing the trial. The judge directed the jury that their verdict declare her guilty. Anthony, forbidden to defend herself until after the verdict, was convicted and fined $100, which she refused to pay. The judge purposely did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her opportunity to appeal her case. Anthony was hoping an appeal could make its way to the US Supreme Court. Although her plan did not materialize, the trial made national headlines and expanded discussion of the movement.

Recording Women’s History

During the 1880s, Anthony focused on documenting the history of the movement she helped create. Recording women’s history for future generations was a project that had been in the minds of Anthony and Stanton for a long time. Both looked upon women’s fight for political participation as a potent force in strengthening democracy and one to be emphasized in history. Anthony was convinced that if women close to the facts did not record them now, they would be forgotten and misinterpreted by future historians (Lutz 164).

Anthony, Stanton, and Matilda Joslin Gage published the History of Woman Suffrage Volume I in 1881, followed by Volumes II, II, and IV in 1882, 1885, and 1902. As Stanton stated, “We have furnished the bricks and mortar for some future architect to rear a beautiful edifice.” (Lutz 166

In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association, which was advocating for state-by-state enfranchisement of women. Stanton became the first president of the new organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, with Anthony subsequently elected its president in 1892. Anthony was also instrumental in creating the International Council of Women and in assisting in organizing the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

In 1898, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, A Story of the Evolution of the Status of Women was published by Ida Husted Harper at Anthony’s request. Anthony also created a press bureau to increase coverage of women's suffrage in the national and local press. This same year, Anthony announced her intention to retire from the National American Association. During the last year of her presidency, she warned the new generation of suffragists not to expect their cause to triumph merely because it was just. After Anthony’s retirement, Carrie Chapman Catt was elected as the new president of the organization. Anthony remarked “New conditions bring new duties. These new duties, these changed conditions, demand stronger hands, younger heads, and fresher hearts. In Mrs. Catt, you have my ideal leader. I present to you my successor.” (Lutz 197)

In 1905, she met with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington DC to discuss the submission of a suffrage amendment to Congress. She attended hearings in DC and gave her “Failure is Impossible” speech at her 86th birthday celebration. “There have been others also just as true and devoted to the cause - I wish I could name every one - but with such women consecrating their lives, failure is impossible!” (Sherr 234)

Susan B. Anthony died on March 13, 1906 from heart failure and pneumonia at her Rochester home. She did not live to see the passage of the 19th Amendment. However, in recognition of her role in bringing about its fruition, the amendment was widely heralded as the “Susan B. Anthony amendment” and was ratified in 1920. As such, it stood as a tribute to Anthony’s integrity, determination, and influence. The fruits of her labor would enable many women to play an integral role in shaping US society for generations to come.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

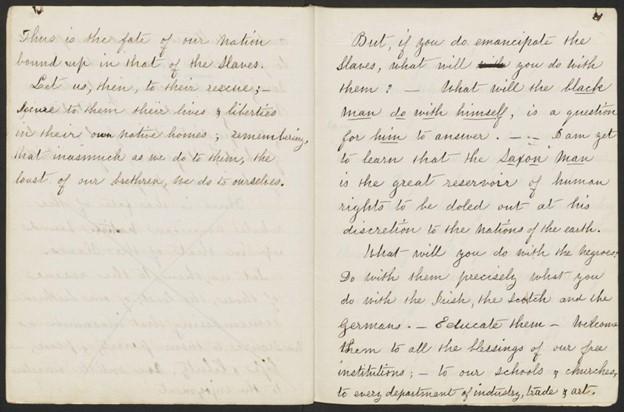

Excerpt from Speech on Abolition 1862

Caption: A handwritten excerpt from speech Anthony gave on slavery in 1862.

Analysis Questions:

- Look at the date of this speech. What is the historical context?

- How would Anthony’s upbringing in the Quaker faith impact her views towards slavery and civil rights for enslaved Africans and African Americans?

- Based on this excerpt, would you expect Anthony to support African American suffrage (the right to vote)?

Educator Notes:

Text of speech:

“What will you do with the Negroes? Do with them precisely what you would do with the Irish, the Scotch, and the Germans - Educate them. Welcome them to all the blessings of our free institutions; - to our schools & churches; to every department of industry, trade, and art. Do with the Negroes? What arrogance in us to put the question, what shall we do with a race of men and women who have fed, clothed, and supported both themselves and their oppressors for centuries.”

Educators can use the Teaching with Primary Sources Teachers Guide: Analyzing Manuscripts to build learner inquiry around this specific section of Anthony’s speech and explore more using the specific questions below.

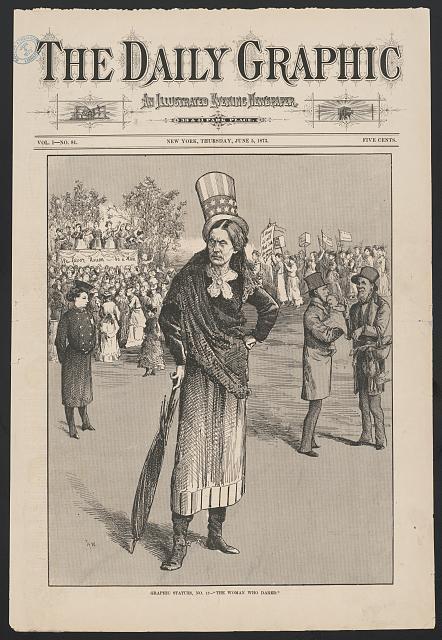

Caption: This satirical cartoon of Susan B. Anthony appeared on the front page of the June 5, 1873 edition of New York’s The Daily Graphic: An Illustrated Evening Newspaper. The illustration was connected to an article about Anthony’s upcoming trial for voting in the 1872 presidential election.

Analysis Questions:

- Observe Anthony and her accessories. How does the artist visually portray her?

- Examine the figures on both sides in the background. What message do you think the artist is trying to portray with these figures?

- Do you think the artist supported the suffrage movement? Why or why not?

Educator Notes:

Learn more about the cartoon here: The Woman Who Dared - Encyclopedia Virginia

Educators can start staging their inquiry of this political cartoon using the Teaching with Primary Sources Teacher Guide: Analyzing Political Cartoons from the Library of Congress and explore more using the specific questions below.

Caption: This cartoon was created to celebrate the annual convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. It shows Wyoming and Utah as angelic maidens flanking George Washington and two suffrage leaders: Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Analysis Questions:

- Define apotheosis.

- Identify the three main figures in the center. Why are they included together?

- What objects are the figures holding and what do they represent?

- Identify the two figures on each side. Why are they significant?

Educator Notes:

Political Cartoon Explanations by Rebekah Clark: https://utahwomenshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/7th-Grade-Cartoon-Explanations_v2.pdf

Educators can start staging their inquiry of this political cartoon using the Teaching with Primary Sources Teacher Guide: Analyzing Political Cartoons from the Library of Congress and explore more using the specific questions below.

- Harper, Ida Husted. Women’s History of Suffrage, Volume V. National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/29878/pg29878-images.html

- International Council of Women. “Report of the International Council of Women.” Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Harvard University. 1888, digitized 2007. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/women-working-1800-1930/catalog/45-990022073280203941.

- Lutz, Alma. Susan B. Anthony: Rebel, Crusader, Humanitarian. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20439/20439-h/20439-h.htm%20Additional%20.

- Sherr, Lynn. Failure Is Impossible : Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words. New York :Times Books, 1995.

- Citation for quote: Anthony, Susan B. "Women's Right to Vote." In The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, edited by Ida H. Harper, Vol. 2, 977-992. Indianapolis and Kansas City: The Bowen-Merrill Company, 1898.

- Citation for cover image: C.M. Bell, photographer. Anthony, Susan B., 1891. March 2. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016689513/.

MLA – Mathias, Marisa. “Susan B. Anthony.” National Women’s History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago – Mathias, Marisa. “Susan B. Anthony.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/susan-brownell-anthony.

Web Sites:

- Crusade for the Vote, National Women's History Museum

- Rights for Women, National Women's History Museum

- Feminism: The First Wave | National Women's History Museum

- From the Declaration of Independence to the Declaration of Sentiments | National Women's History Museum

- Susan B. Anthony House

- 1873 Speech of Susan B. Anthony on woman suffrage

- Susan B. Anthony House, National Park Service

- Susan B. Anthony, National Women's Hall of Fame

- Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Project

- Public Broadcasting System (PBS) - "Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony"

- The Power of Words and Activism | National Women's History Museum

- Trial of Susan B. Anthony

Books:

- Anthony, Susan B. The Trial of Susan B. Anthony (Humanity Books, 2003).

- Anthony, Katherine Susan. Susan B. Anthony: Her Personal History and Her Era (Russell & Russell, 1975).

- Barry, Kathleen. Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist (Authorhouse, 2000).

- Dubois, Ellen Carol. The Elizabeth Cady Stanton-Susan B. Anthony Reader: Correspondences, Writings and Speeches (Boston: Northeaster University Press, 1992).

- Harper, Ida. Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony (Beaufort books - 3 volume set).

- Isaacs, Sally Senzell. America in the Time of Susan B. Anthony: The Story of Our Nation from Coast to Coast (Heinemann Library, 2000).

- Monsell, Helen Albee. Susan B. Anthony: Champion Women's Rights (Aladdin, 1986).

- Sherr, Lynn. Failure is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words (Three Rivers Press, 1996).

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Ann De Gordon, and Susan B. Anthony. Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: In the School of Anti-Slavery, 1840-1866 (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997).

- Ward, Geoffery C. and Ken Burns. Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (Knopf, 2001).

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact [email protected].